The EU and India just did something the apparel trade has been talking about for two decades: they closed a free trade agreement. Not a “framework.” Not a “roadmap.” A deal. And if you work in textiles and apparel, you already know why this matters: Europe still taxes clothing like it’s a vice, and that tax has been one of the quiet levers shaping sourcing decisions for years.

On paper, the headline is simple. The EU–India agreement removes most tariffs on textiles and apparel at entry into force. In plain English, it’s designed to take Indian apparel and home textiles — much of it still paying up to roughly 12% in tariffs at the EU border — and move them much closer to a zero-duty world.

But the real implications won’t show up in a press conference photo. They’ll show up in cost sheets, vendor nominations, and the quiet emails buyers send when they want “options.” They’ll show up in Dhaka and Faisalabad and Tiruppur, and — yes — in Washington, because this deal lands at a moment when US trade policy is doing the opposite of what Europe is doing: raising walls, not lowering them.

Sure, the U.S. and India announced a trade deal to reduce tariffs to 18%, but the details of the agreement have yet to be released. The deal is predicated on India dropping Russia as an oil supplier. How will that work? Will it take time? Politics could come roaring back if these details aren’t clearly defined.

The 12% problem and why it changes behavior fast

Back to the EU-India FTA. In apparel, 12% isn’t a rounding error. It’s the difference between being on the short list and being the “nice backup.” It’s the reason buyers squeeze factories that are otherwise competitive. It’s the math behind why two suppliers with similar workmanship can live in different universes once landed costs are applied.

Europe’s tariff structure has rewarded countries with preferences and punished those without them. Bangladesh has benefited from duty-free access to the EU under the Everything But Arms (EBA) initiative. Pakistan has benefited from the EU’s GSP+ program, which cuts duties to zero on more than two-thirds of tariff lines for eligible countries. And Pakistan is explicitly one of those beneficiaries. India, by contrast, has spent years competing in Europe while paying more duty than its direct rivals.

Also Read: India-Bangladesh CEPA/FTA: Opportunities and Risks for Bangladesh’s Apparel Sector

That imbalance got even sharper on January 1st, when a large share of India’s EU GSP tariff preferences were suspended through the end of 2028 under EU “graduation” rules, meaning Indian exporters in sensitive categories shifted to full MFN rates right as the FTA was being finalized. So the timing is awkward: India loses a chunk of preference first, then wins a bigger one, once the FTA actually enters into force.

What changes immediately is buyer psychology. The moment a real FTA is on the horizon, brands start planning capacity and relationships as if the duty relief is already “banked.” They don’t wait for the last signature. They develop the vendor base now so they can flip volume the day the tariff line turns to zero.

Rules of origin: where trade deals live or die

Tariffs are the headline. Rules of origin are the trap door.

The EU’s own chapter-by-chapter summary makes the point directly: tariff preferences only apply to goods that are “significantly processed” in one of the parties, and the agreement relies on modern origin documentation that includes self-certification and verification tools. That sounds procedural, but for textiles and apparel, it’s everything because “origin” is basically a map of your supply chain.

If the origin rules require meaningful transformation, what the European textile industry has historically pushed for as “double transformation” principles, then you don’t win Europe by being a simple cut-and-sew platform. You win by being integrated: yarn, fabric, dyeing/finishing, and garment, with traceable documentation that survives an audit.

This is where India’s structure matters. India has depth across spinning, weaving/knitting, processing, and garmenting. When managed well, it can meet stricter origin thresholds in ways some competitors struggle to at scale. And if the EU–India rules are aligned with “recent EU FTAs,” as the EU says they are, then the deal rewards suppliers that can prove origin cleanly, not just quote a price.

So the FTA is not just “India gets cheaper into Europe.” It’s “India gets cheaper into Europe if India can document the chain.” That’s a different game than the old preference model, where duty-free access often papered over weak upstream capability.

Bangladesh: still duty-free, but the clock is no longer theoretical

Bangladesh is the largest beneficiary of the EU’s EBA preferences, and the EU’s own trade page is blunt about what the relationship looks like: EU imports from Bangladesh are dominated by textiles, and EBA has been the backbone of that flow. For years, Bangladesh has held a structural advantage in Europe because duties were effectively removed from the equation.

That advantage is not permanent. Bangladesh is scheduled to graduate from the UN’s least developed country status on November 24th. The EU has discussed a transition period that preserves EBA-style access for a limited time, with many analysts and regional reporting pointing to continued preference through November 2029 before the real cliff arrives.

Here’s what buyers do with that information: they hedge. Not because Bangladesh is “done.” Bangladesh remains a scale machine, and it has built real capability and compliance infrastructure since Rana Plaza—often under pressure from the EU and other partners. But because buyer calendars run years ahead. If you’re a European brand placing long-term bets, you don’t want a single country’s preference status to be your strategy.

The EU–India FTA gives Europe a clean hedge. It allows buyers to deepen India programs now, especially in categories where India already performs well (home textiles, cotton products, knits, value-added programs), so that if Bangladesh faces a post-2029 duty shock, there is a credible, scaled alternative ready to absorb volume.

Pakistan: GSP+ advantage narrows, and the compliance risk stays

Pakistan’s situation is different from Bangladesh’s, but the vulnerability is similar: preference dependence.

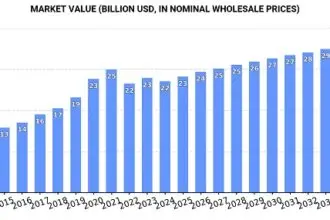

Under GSP+, Pakistan benefits from duty-free treatment on a large share of tariff lines, tied to compliance with 27 international conventions on human rights, labor rights, the environment, and governance. The EU notes that the current GSP+ framework is valid until 2027. That matters because Pakistan’s textile and apparel exports to Europe have leaned heavily on the program’s tariff relief, and industry-level assessments show just how large the EU market is for Pakistani textiles and clothing.

The EU–India FTA compresses Pakistan’s advantage. If India reaches zero duty on many apparel lines into the EU, Pakistan is no longer “the duty-free South Asian option” by default. It becomes one of several duty-free options, and buyers will shift the discussion back to performance: lead times, product development, quality consistency, and compliance transparency.

And then there’s the risk Pakistan cannot diversify away from: GSP+ is conditional and subject to review. Even when it continues, it comes with monitoring and political scrutiny by design. An FTA is typically harder to unwind than a preference program. So even if nothing dramatic happens to Pakistan’s status in the near term, buyers can rationally see India’s FTA access as more “durable” than Pakistan’s preference access.

Europe opens a door while Washington raises a toll booth

Now, the US angle — and this is where the geopolitics finally hits the factory floor.

India’s textile and apparel exporters are leaning into Europe after being hit by 50% US tariffs imposed in August 2025, with the US still described as India’s top textile market (28% of exports) and the EU second. That is the definition of a sourcing squeeze: one market becomes punitive, the other becomes more accessible.

If you want to know how trade agreements change trade relations, watch what happens next. India will push harder to diversify away from the US, because it must. Europe becomes the pressure valve. And if Europe is offering a pathway to eliminate duties on textiles and apparel, the EU effectively becomes the “growth market” for Indian exporters at the exact moment the US becomes the “risk market.”

Also Read: The Triple Threat to Brand Profitability and Growth: What Boards Need to Know

For US brands and US policymakers, that’s a strategic self-own. The US has spent years talking about “friendshoring,” “de-risking,” and reducing exposure to China. India is the obvious candidate in that narrative. But if the US response is punitive tariffs while Europe signs a comprehensive deal, the result is simple: Europe gets first call on India’s best capacity expansions, especially the ones that can meet tighter origin and compliance requirements.

And yes, that bleeds into broader US–EU trade relations. Europe is building rules-based access and locking in supply chain relationships; the US is signaling uncertainty and cost. That divergence will show up in where investment goes—spinning, processing, compliance systems, traceability platforms because factories invest where the market signals stability.

The real winners and losers, and what to watch next

The winner is not a country. It’s the buyer with optionality.

The EU–India FTA increases optionality in Europe, and optionality is power. Buyers will use it to negotiate pricing from everyone: India, Bangladesh, Pakistan, Turkey, even Vietnam and other FTA-equipped suppliers. The deal doesn’t end competition; it intensifies it.

The losers are the suppliers who mistake tariff preference for a business model. Bangladesh still has time, but it needs a post-2029 plan that is real, either a new preferential pathway or a higher-value proposition that can survive MFN rates. Pakistan needs to treat GSP+ renewal and compliance as a commercial requirement, not a diplomatic exercise, because “duty-free” means nothing if customers don’t trust the governance risk.

What to watch now is unglamorous, but it’s what decides outcomes:

First, the implementation path. The EU notes that textiles and apparel tariffs are largely removed at entry into force, but entry into force requires process, documentation systems, and enforcement reality.

Second, origin friction. If origin rules are strict and audits are active, integrated players win, and marginal assemblers lose.

Third, compliance load. Europe is not getting softer on labor and sustainability expectations; it’s getting more structured. The factories that can prove their chain cleanly will gain share, and the ones that cannot will watch the opportunity pass by, even with a zero-duty headline.

The EU–India FTA is not a silver bullet. It is a rebalancing of the tariff math that has distorted sourcing for years. It makes India more competitive in Europe, changes the leverage buyers have over Bangladesh and Pakistan, and again exposes the growing gap between how the EU and the US choose to manage trade. If you’re in this business, you don’t have to love any of that to understand what it means.

Because in apparel, the world doesn’t change when politicians announce a deal. It changes when a 12%-line item disappears from sourcing calculations.