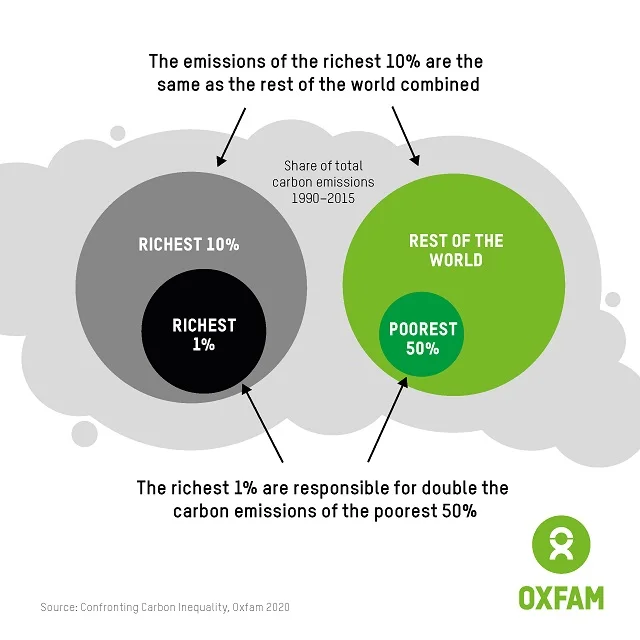

The world’s richest 1 % have already used up their “fair share” of the 2026 global carbon budget in just 10 days, highlighting the disproportionate impact of extreme wealth on climate change and adding pressure on high-emission sectors such as the textile and apparel industry to accelerate decarbonisation, according to a report by Oxfam International. The charity’s analysis also found that the top 0.1 % of the global population exhausted their entire annual carbon allocation by January 3, underlining the urgent need for systemic change in both consumption and production patterns.

Oxfam said the richest individuals are responsible for a disproportionate share of emissions due to their consumption of private jets, luxury yachts, large homes and high-emission investment portfolios. These excess emissions compound the environmental challenges already faced by the textile and apparel sector, which contributes roughly 8 % to 10 % of global greenhouse gas emissions, making it one of the largest industrial contributors to climate change.

Analysts say that the inequality highlighted in the Oxfam report makes it more difficult for industries such as textiles to achieve meaningful emissions reductions. The industry’s footprint spans the full value chain — from fibre production to textile processing, garment manufacturing, transportation and retail — with energy-intensive upstream processes like spinning, weaving, dyeing and finishing accounting for the majority of emissions.

To remain within the Paris Agreement’s 1.5 °C warming limit, Oxfam estimates the richest 1 % must reduce their emissions by nearly 97 % by 2030, while the top 0.1 % would need cuts approaching 99 %. These reductions would require major shifts in lifestyle and investment choices, alongside strengthened climate policy targeting high-emission individuals and corporations.

Also Read: Transforming Agricultural Byproducts into Sustainable Smart Wearables

For the textile and apparel industry, the implications are immediate. Global fashion production emits around 1.2 billion tonnes of CO₂ equivalent annually, driven largely by synthetic fibre production, dyeing, finishing, and global transport of garments. Major apparel companies have pledged net-zero targets and adopted renewable energy and energy-efficiency measures, but the bulk of the industry’s emissions lie in scope 3 — upstream material processing and supplier operations — which remain difficult to reduce without systemic change.

Environmental advocates warn that tackling the textile sector’s footprint requires addressing both industrial emissions and the outsized impact of wealthy consumers. Reducing overconsumption, improving recycling rates, adopting circular economy practices, and extending garment lifespans are among the strategies recommended to curb emissions. Simultaneously, policies targeting high-emission individuals — including carbon pricing, wealth taxes, and regulation of luxury consumption — are increasingly seen as necessary to complement industrial decarbonisation.

The issue is particularly pressing in manufacturing hubs like Bangladesh, India, and Vietnam, where textile and apparel production is a major economic driver. In Bangladesh, for example, the ready-made garment sector supports millions of workers but also contributes significantly to national greenhouse gas emissions. Climate extremes and rising temperatures threaten worker safety, supply chain stability, and overall production resilience, making emissions reductions both an environmental and operational imperative.

Sustainability experts stress that integrated action is needed. “Industry must reduce its own carbon footprint while broader societal emissions are addressed,” said one climate analyst. “If the richest continue to emit at current rates, the sector’s mitigation pathways become far steeper, and targets that seem achievable on paper may remain out of reach in practice.”

As global awareness of climate inequality grows, the Oxfam findings serve as a warning that efforts to decarbonise the textile and apparel industry cannot succeed in isolation. Addressing the excess emissions of the wealthiest alongside systemic reforms in production and consumption is essential to keep the world on track for climate goals and ensure that industries with high environmental impact can operate sustainably in the decades ahead.